Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Reading Comprehension for April 1

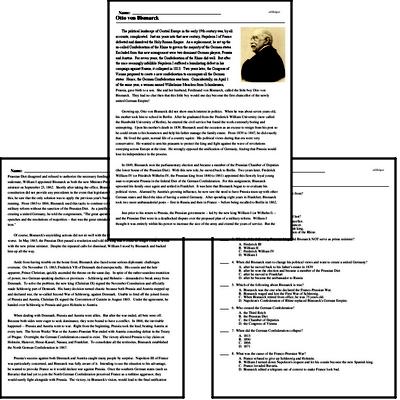

The political landscape of Central Europe in the early 19th century was, by all accounts, complicated. Just six years into that new century, Napoleon I of France defeated and dissolved the Holy Roman Empire. As a replacement, he set up the so-called Confederation of the Rhine to govern the majority of the German states. Excluded from this new arrangement were two dominant German players, Prussia and Austria. For seven years, the Confederation of the Rhine did well. But after the once seemingly infallible Napoleon I suffered a humiliating defeat in his campaign against Russia, it collapsed in 1813. Two years later, the Congress of Vienna proposed to create a new confederation to encompass all the German states. Hence, the German Confederation was born. Coincidentally, on April 1 of the same year, a woman named Wilhelmine Mencken from Schonhausen, Prussia, gave birth to a son. She and her husband, Ferdinand von Bismarck, called the little boy Otto von Bismarck. They had no clue then that this little boy would one day become the first chancellor of the newly united German Empire!

Growing up, Otto von Bismarck did not show much interest in politics. When he was about seven years old, his mother took him to school in Berlin. After he graduated from the Frederick William University (now called the Humboldt University of Berlin), he entered the civil service but found the work extremely boring and uninspiring. Upon his mother's death in 1839, Bismarck used the occasion as an excuse to resign from his post so he could return to his hometown and help his father manage the family estate. From 1839 to 1847, he did exactly that. He lived the quiet, normal life of a country squire. His political views during that era were very conservative. He wanted to arm his peasants to protect the king and fight against the wave of revolutions sweeping across Europe at the time. He strongly opposed the unification of Germany, fearing that Prussia would lose its independence in the process.

In 1849, Bismarck won the parliamentary election and became a member of the Prussian Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of the Prussian Diet). With this new role, he moved back to Berlin. Two years later, Frederick William IV (or Friedrich Wilhelm IV, the Prussian king from 1840 to 1861) appointed this fiercely loyal young man to represent Prussia in the federal Diet of the German Confederation. For this assignment, Bismarck uprooted his family once again and settled in Frankfurt. It was here that Bismarck began to re-evaluate his political views. Alarmed by Austria's growing influence, he now saw the need to have Prussia team up with other German states and liked the idea of having a united Germany. After spending eight years in Frankfurt, Bismarck took two more ambassadorial posts -- first in Russia and then in France -- before being recalled to Berlin in 1862.

Just prior to his return to Prussia, the Prussian government -- led by the new king William I (or Wilhelm I) -- and the Prussian Diet were in a deadlocked dispute over the proposed plan of a military reform. William I thought it was entirely within his power to increase the size of the army and extend the years of service. But the Prussian Diet disagreed and refused to authorize the necessary funding for the reform. Hoping to break the stalemate, William I appointed Bismarck as both the new Minister-President (prime minister) and the new foreign minister on September 23, 1862. Shortly after taking the office, Bismarck boldly declared that the current constitution did not provide any precedents in the event that legislators failed to approve a budget. Because of this, he saw that the only solution was to apply the previous year's budget in order to keep the government running. From 1863 to 1866, Bismarck used this tactic to continue collecting taxes and spending the money on military reform without the sanction of the Prussian Diet. As a justification for the reform and a prelude to creating a united Germany, he told the congressmen, "The great questions of the day will not be decided by speeches and the resolutions of majorities -- that was the great mistake from 1848 to 1849 -- but by blood and iron."

Of course, Bismarck's unyielding actions did not sit well with the Prussian Diet. Soon the situation got even worse. In May 1863, the Prussian Diet passed a resolution and told the king that it could no longer come to terms with the new prime minister. Despite the repeated calls for dismissal, William I stood by Bismarck and backed him up all the way.